IDF

Evaluating CMR - Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes/CVD RiskKey Points

- Waist girth is a mandatory feature of International IDF clinical criteria for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome.

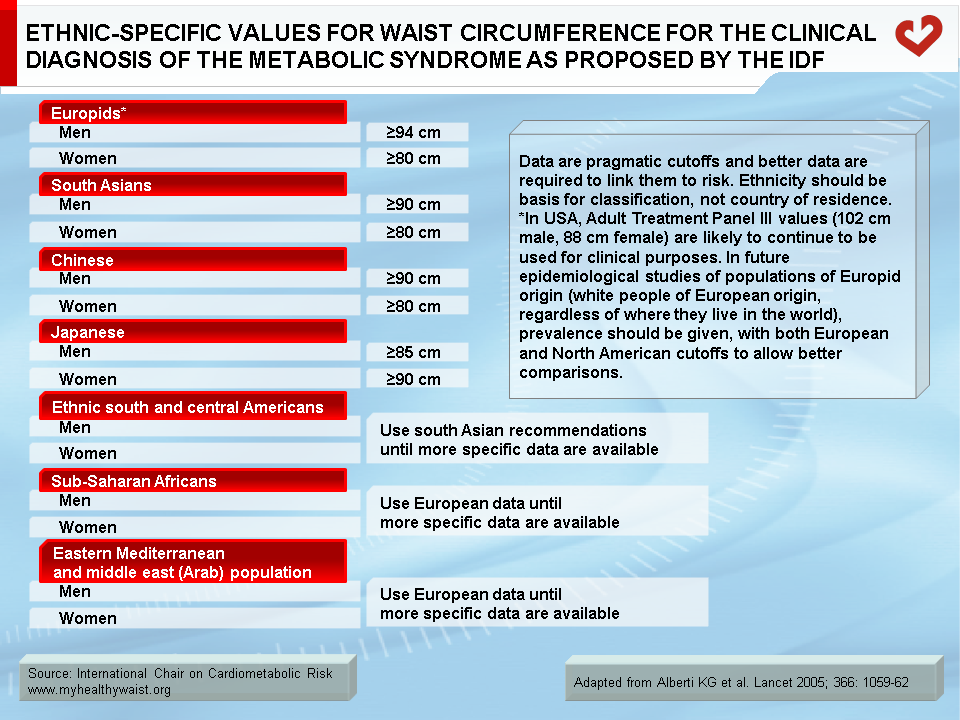

- For the first time, population-specific cutoffs have been proposed to consider ethnic differences in the relationship between abdominal obesity and incidence of CHD and type 2 diabetes.

- IDF clinical criteria are similar to those proposed by the NCEP-ATP III regarding metabolic markers used to diagnose the metabolic syndrome.

- When managing the metabolic syndrome, the first step should be to reduce visceral adipose tissue through lifestyle modification.

- Most prospective studies have found a positive relationship between the metabolic syndrome (IDF criteria) and CVD.

- Further research is required to establish specific waist circumference cutoffs for all regions of the world.

IDF Clinical Criteria for Diagnosing the Metabolic Syndrome

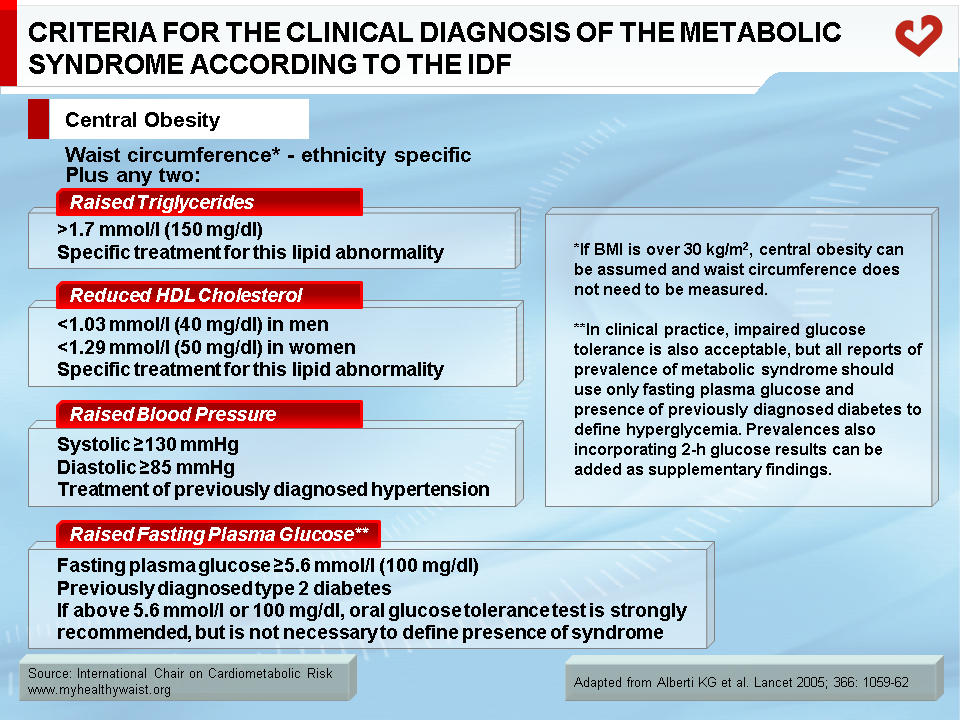

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) clinical criteria for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome were proposed in 2005 (Table 1) [1,2]. These criteria provide a new screening strategy for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome in clinical practice and are not a new “definition” of the syndrome. These screening tools are similar to those proposed by the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III or ATP III). However, since the clinical criteria of many organizations did not consider ethnic differences in body fat distribution and susceptibility to visceral adiposity, the IDF committee proposed ethnic-specific waist cutoff values (Table 2). For instance, some ethnic groups, such as Asians, are more likely to develop complications of the metabolic syndrome at much lower waist circumference than Caucasians [3].

Screening tools that do not consider ethnicity may therefore over or underestimate the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome depending on the population studied. The early waist cutoff values initially proposed by NCEP-ATP III did not encompass all Asian individuals with the metabolic syndrome, who on average have lower waist circumference values than Caucasians. Accordingly, waist circumference thresholds have been lowered in the IDF statement. The other major advance ushered in by the IDF criteria is that waist circumference is now a mandatory feature in identifying the metabolic syndrome. Individuals diagnosed with the metabolic syndrome must have an elevated waist girth plus at least two other features, which are comparable to those proposed by NCEP-ATP III. By taking this stance, the IDF recognizes that abdominal obesity is by far the most prevalent form of the metabolic syndrome seen in clinical practice.

Etiology and Treatment of the Metabolic Syndrome and its Components According to the IDF

IDF clinical criteria for the metabolic syndrome acknowledge that abdominal obesity and insulin resistance are pivotal causal factors. To assess abdominal obesity, the IDF suggests measuring waist circumference because it is independently associated with every single marker of the metabolic syndrome and because viscerally obese individuals are at much greater risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type 2 diabetes at any body mass index (BMI) level [4-6]. Compared to NCEP-ATP III clinical criteria, IDF criteria set out lower cutoffs in men and women of any ethnicity. However, NCEP-ATP III has also suggested that individuals with a waist circumference slightly below the proposed cutoffs could still be at increased risk of developing or having the metabolic syndrome if they have at least two other clinical criteria. This suggests that IDF and NCEP-ATP III waist circumference criteria do not differ substantially. For individuals with a BMI above 30 kg/m2, the IDF states that there is no need to measure waist circumference since 95% of obese individuals are likely to have a waist circumference above proposed cutoff values [7]. Further research is clearly required in this area, especially in regions were few population studies are available to study the relationship between waist circumference, metabolic syndrome, and CVD and type 2 diabetes risk. For treatment of obesity, the IDF suggests adopting healthy lifestyle habits that include regular physical activity or exercise. The key goal for individuals with the metabolic syndrome should be moderate weight loss (5 to 10% of initial body weight). Moderate caloric restriction combined with increased physical activity yields optimal results. According to the IDF, patients should strive to perform at least 180 minutes of moderate physical activity and at least 60 minutes of vigorous physical activity per week. In terms of nutrition, the IDF recommends decreasing total fat intake, modifying diet composition to increase fibre intake, and reducing intake of saturated fats and sodium.

The IDF recognizes atherogenic dyslipidemia as an important component of the metabolic syndrome. Dyslipidemic patients with the metabolic syndrome are characterized by a cluster of lipid abnormalities such as elevated triglyceride and apolipoprotein B concentrations as well as low HDL cholesterol. Hypertriglyceridemia has been shown to decrease both LDL and HDL particle size [8]. The IDF proposed the same triglyceride and HDL cholesterol cutoff values as NCEP-ATP III and stated that other HDL cholesterol cutoff values may be required for women in certain populations [9]. With respect to treating the atherogenic dyslipidemia of the metabolic syndrome, the IDF agrees that LDL cholesterol levels should be the primary target of therapy. Statins have been shown to significantly decrease LDL cholesterol levels and, more importantly, reduce the risk of a first or recurrent coronary heart disease (CHD) event [10]. These compounds might also have other pleiotropic effects, such as reducing apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins and non-HDL cholesterol (VLDL, IDL, and LDL cholesterol) levels, which are also important therapeutic targets. Similarly, fibric acid derivatives can increase HDL cholesterol levels and reduce major coronary events incidence in patients with established CHD. Fibrate therapy may therefore be another compelling treatment for the atherogenic dyslipidemia of the metabolic syndrome [11].

In determining its clinical criteria for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome, the IDF suggested that high blood pressure is defined by systolic blood pressure ≥130 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure ≥85 mm Hg or by treatment for hypertension. The IDF also states that while endothelial dysfunction and microalbuminuria are components of vascular dysregulation beyond elevated blood pressure, further research is needed to link these conditions to the metabolic syndrome. Regarding treatment of elevated blood pressure, the IDF supports national recommendations, i.e., drug therapy is required for patients with a blood pressure ≥140/≥90 mm Hg [12]. No specific pharmacological treatment was proposed for elevated blood pressure.

As demonstrated in the Bruneck study, insulin resistance is a very common feature of the metabolic syndrome and its associated diabetic dyslipidemia [13]. Although insulin resistance is closely associated with the metabolic syndrome, fasting glucose (a marker of insulin resistance) is not a mandatory criterion for diagnosing the metabolic syndrome. The proposed cutoff value is 5.6 mmol/l (100 mg/dl) (or previously diagnosed diabetes), as suggested by the American Diabetes Association [14]. If fasting glycemia is between 6.1 (110 mg/dl) and 6.9 mmol/l (125 mg/dl), the IDF suggests performing an oral glucose tolerance test to diagnose impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes [15]. The IDF calls on insulin-resistant patients to adopt a healthy lifestyle, highlighting the fact that subjects in the Diabetes Prevention Program and Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study who modified their lifestyle were able to reduce or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes [16,17].

Regarding the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic profile, the IDF singles out the inflammatory marker C-reactive protein, which is positively associated with insulin resistance and obesity, as a common feature of the metabolic syndrome [18]. Components of the pro-thrombotic profile of the metabolic syndrome include fibrinolytic factors such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. The IDF also believes that further research is required in this area, as other adipokines resulting from the macrophage infiltration of adipose tissue, such as tumour necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6, are thought to significantly influence the insulin resistance tied to visceral adipose tissue and the related inflammatory state. The mechanisms by which fibrinolytic and clotting factors such as fibrinogen are associated with the metabolic syndrome need further clarification. For more information, please refer to Complications of Visceral Obesity and Managing CMR sections.

IDF Clinical Tools for Diagnosing the Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes/CVD Risk

One of the most important studies to tie the metabolic syndrome (as diagnosed by the IDF) to CVD mortality is the Diabetes Epidemiology: Collaborative analysis Of Diagnostic criteria in Europe (DECODE) Study. A total of 4,715 men and 5,554 women 30 to 89 years of age were drawn from nine European population-based cohorts [19]. The maximum follow-up periods ranged from 7 to 16 years. Metabolic syndrome prevalence was 35.9% in men and 34.1% in women. Hazard ratios (HR) were estimated using Cox regression analysis. A total of 105 men with the metabolic syndrome died from CVD, and the unadjusted HR was 1.79 (95% CI, 1.36-2.36). A total of 47 women with the metabolic syndrome died from CVD (the unadjusted HR for women was 2.38; 95% CI, 1.55-3.65). The DECODE Study also looked at the relationship between World Health Organization (WHO) clinical criteria, NCEP-ATP III guidelines, and revised NCEP-ATP III guidelines. Study findings are summarized in the Comparison of Screening Tools section.

Interestingly, a cohort study of 4,350 Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes failed to find a positive association between the metabolic syndrome as defined by the IDF and CHD (myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, coronary revascularization, heart failure, and CHD-related death) [20]. Median study follow-up was 7.1 years. Compared to subjects without the metabolic syndrome, the HR for individuals with the metabolic syndrome (as identified by the IDF) was 1.13 (95% CI, 0.86-1.48). However, the authors reached different conclusions with NCEP-ATP III clinical criteria, as discussed in the Comparison of Screening Tools section. After adjusting for confounding variables, the best predictors of incident CHD in this diabetic population were systolic blood pressure and HDL cholesterol levels.

During the 10-year follow-up of the Strong Heart Study, 1,561 men and 2,384 women with and without diabetes were screened for the presence of the metabolic syndrome using a number screening tools [21]. With the IDF criteria, metabolic syndrome prevalence at the beginning of follow-up was 59% and 73% for men and women, respectively. After adjusting for age, sex, and field centre, non-diabetic subjects who met IDF clinical criteria for the metabolic syndrome had a HR for incident fatal or non-fatal CVD of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.22-1.66, p<0.001). For subjects with diabetes, the HR for incident CVD was 2.59 (95% CI, 2.25-2.98, p<0.001).

To assess CHD risk related to the metabolic syndrome, Bataille et al. [22] conducted a nested case-control study in the PRIME (étude PRospective de l’Infarctus du MyocardE-Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction) cohort. The PRIME study was conducted in Northern Ireland (Belfast) and France, particularly in Lille (North), Strasbourg (East), and Toulouse (Southwest). The study sample included 296 cases of incident CHD and 540 CHD-free controls, all of whom were men 50 to 59 years of age. The study follow-up was five years. When IDF clinical criteria for the metabolic syndrome were used, the metabolic syndrome was prevalent in 38.9% of cases and 32.4% of controls. When the data was analyzed separately (Ireland and France), the odds ratio (OR) for future CHD was not significant. However, when the entire sample was studied, the future CHD OR for individuals with IDF clinical criteria for the metabolic syndrome was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.02-1.95, p<0.04). The findings were very similar when the WHO and NCEP-ATP III clinical criteria were compared.

In the Hong Kong Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence Study, Cheung et al. [23] studied the association between IDF and NCEP-ATP III metabolic syndrome criteria and diabetes incidence in 1,679 men and women (mean age: 45.1 ± 11.9 years) without diabetes at baseline who were followed for six years. There were 120 new onset diabetes cases during follow-up. The HR for diabetes incidence was 3.5 (95% CI, 2.3-5.2) when IDF clinical criteria were used. The authors suggested that the presence of the metabolic syndrome in someone without diabetes should be a strong warning sign. Moreover, lowering abdominal obesity cutoff values in this Asian population appeared to be justified given that the area under the receiver operating characteristic curves tended to be higher in both men and women when lower waist circumference cutoffs were used.

It is important to mention that although the presence of the metabolic syndrome increases relative risk of CVD/CHD, it diagnosis cannot be used to assess absolute CVD/CHD risk. This can only be done by taking into account traditional CHD risk factors such as age, sex, LDL and HDL cholesterol, blood pressure, smoking, and diabetes. However, clinical diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome can “fine tune” CHD risk prediction on top of traditional risk factors. It is not designed to replace these risk factors, as discussed in other sections.

In summary, IDF clinical criteria for the diagnostic of the metabolic syndrome include mandatory inclusion of the waist circumference measurement. Region-specific cutoff values have now been proposed since the relationship of abdominal obesity to CHD or type 2 diabetes varies between ethnic groups. Additional studies are needed to further validate these new criteria and their ties to hard CHD endpoints. Moreover, specific cutoff values will be required for Central American, Sub-Saharan African, and Middle Eastern countries that were not considered in the IDF criteria due to lack of specific data. A review paper has summarized the assessment, management and prevention of metabolic syndrome in individuals from various ethnic groups [24].

For more information, please visit the IDF website at https://www.idf.org/.

References

-

The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. https://www.idf.org/e-library/consensus-statements/60-idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolic-syndrome.html, last accessed in November, 2020.

PubMed ID:

-

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome–a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059-62.

PubMed ID: 16182882

-

Tan CE, Ma S, Wai D, et al. Can we apply the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel definition of the metabolic syndrome to Asians? Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1182-6.

PubMed ID: 15111542

-

Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, et al. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 2004; 53: 2087-94.

PubMed ID: 15277390

-

Ohlson LO, Larsson B, Svardsudd K, et al. The influence of body fat distribution on the incidence of diabetes mellitus. 13.5 years of follow-up of the participants in the study of men born in 1913. Diabetes 1985; 34: 1055-8.

PubMed ID: 4043554

-

Pouliot M-C, Després JP, Lemieux S, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagitttal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol 1994; 73: 460-8.

PubMed ID: 8141087

-

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med 2006; 23: 469-80.

PubMed ID: 16681555

-

Carr MC and Brunzell JD. Abdominal obesity and dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome: importance of type 2 diabetes and familial combined hyperlipidemia in coronary artery disease risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 2601-7.

PubMed ID: 15181030

-

Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285: 2486-97.

PubMed ID: 11368702

-

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005; 112: 2735-52.

PubMed ID: 16157765

-

Robins SJ, Rubins HB, Faas FH, et al. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular events with low HDL cholesterol: the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1513-7.

PubMed ID: 12716814

-

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42: 1206-52.

PubMed ID: 14656957

-

Bonora E, Kiechl S, Willeit J, et al. Prevalence of insulin resistance in metabolic disorders: the Bruneck Study. Diabetes 1998; 47: 1643-9.

PubMed ID: 9753305

-

Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3160-7.

PubMed ID: 14578255

-

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. International Diabetes Federation: a consensus on Type 2 diabetes prevention. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 451-63.

PubMed ID: 17470191

-

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393-403.

PubMed ID: 11832527

-

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343-50.

PubMed ID: 11333990

-

Lemieux I, Pascot A, Prud’homme D, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein: another component of the atherothrombotic profile of abdominal obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21: 961-7.

PubMed ID: 11397704

-

Qiao Q. Comparison of different definitions of the metabolic syndrome in relation to cardiovascular mortality in European men and women. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 2837-46.

PubMed ID: 17021922

-

Tong PC, Kong AP, So WY, et al. The usefulness of the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III definitions of the metabolic syndrome in predicting coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1206-11.

PubMed ID: 17259472

-

de Simone G, Devereux RB, Chinali M, et al. Prognostic impact of metabolic syndrome by different definitions in a population with high prevalence of obesity and diabetes: the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1851-6.

PubMed ID: 17440172

-

Bataille V, Perret B, Dallongeville J, et al. Metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease risk in a population-based study of middle-aged men from France and Northern Ireland. A nested case-control study from the PRIME cohort. Diabetes Metab 2006; 32: 475-9.

PubMed ID: 17110903

-

Cheung BM, Wat NM, Man YB, et al. Development of diabetes in Chinese with the metabolic syndrome: a 6-year prospective study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1430-6.

PubMed ID: 17337491

-

Lear SA and Gasevic D. Ethnicity and metabolic syndrome: implications for assessment, management and prevention. Nutrients 2019; 12: 15.

PubMed ID: 31861719

CLOSE

CLOSE

The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome. https://www.idf.org/e-library/consensus-statements/60-idfconsensus-worldwide-definitionof-the-metabolic-syndrome.html, last accessed in November, 2020.

PubMed ID: CLOSE

CLOSE

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome–a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059-62.

PubMed ID: 16182882 CLOSE

CLOSE

Tan CE, Ma S, Wai D, et al. Can we apply the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel definition of the metabolic syndrome to Asians? Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1182-6.

PubMed ID: 15111542 CLOSE

CLOSE

Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, et al. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 2004; 53: 2087-94.

PubMed ID: 15277390 CLOSE

CLOSE

Ohlson LO, Larsson B, Svardsudd K, et al. The influence of body fat distribution on the incidence of diabetes mellitus. 13.5 years of follow-up of the participants in the study of men born in 1913. Diabetes 1985; 34: 1055-8.

PubMed ID: 4043554 CLOSE

CLOSE

Pouliot M-C, Després JP, Lemieux S, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagitttal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol 1994; 73: 460-8.

PubMed ID: 8141087 CLOSE

CLOSE

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A Consensus Statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med 2006; 23: 469-80.

PubMed ID: 16681555 CLOSE

CLOSE

Carr MC and Brunzell JD. Abdominal obesity and dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome: importance of type 2 diabetes and familial combined hyperlipidemia in coronary artery disease risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 2601-7.

PubMed ID: 15181030 CLOSE

CLOSE

Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA 2001; 285: 2486-97.

PubMed ID: 11368702 CLOSE

CLOSE

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005; 112: 2735-52.

PubMed ID: 16157765 CLOSE

CLOSE

Robins SJ, Rubins HB, Faas FH, et al. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular events with low HDL cholesterol: the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 1513-7.

PubMed ID: 12716814 CLOSE

CLOSE

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension 2003; 42: 1206-52.

PubMed ID: 14656957 CLOSE

CLOSE

Bonora E, Kiechl S, Willeit J, et al. Prevalence of insulin resistance in metabolic disorders: the Bruneck Study. Diabetes 1998; 47: 1643-9.

PubMed ID: 9753305 CLOSE

CLOSE

Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003; 26: 3160-7.

PubMed ID: 14578255 CLOSE

CLOSE

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. International Diabetes Federation: a consensus on Type 2 diabetes prevention. Diabet Med 2007; 24: 451-63.

PubMed ID: 17470191 CLOSE

CLOSE

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 393-403.

PubMed ID: 11832527 CLOSE

CLOSE

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343-50.

PubMed ID: 11333990 CLOSE

CLOSE

Lemieux I, Pascot A, Prud’homme D, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein: another component of the atherothrombotic profile of abdominal obesity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21: 961-7.

PubMed ID: 11397704 CLOSE

CLOSE

Qiao Q. Comparison of different definitions of the metabolic syndrome in relation to cardiovascular mortality in European men and women. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 2837-46.

PubMed ID: 17021922 CLOSE

CLOSE

Tong PC, Kong AP, So WY, et al. The usefulness of the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program’s Adult Treatment Panel III definitions of the metabolic syndrome in predicting coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1206-11.

PubMed ID: 17259472 CLOSE

CLOSE

de Simone G, Devereux RB, Chinali M, et al. Prognostic impact of metabolic syndrome by different definitions in a population with high prevalence of obesity and diabetes: the Strong Heart Study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1851-6.

PubMed ID: 17440172 CLOSE

CLOSE

Bataille V, Perret B, Dallongeville J, et al. Metabolic syndrome and coronary heart disease risk in a population-based study of middle-aged men from France and Northern Ireland. A nested case-control study from the PRIME cohort. Diabetes Metab 2006; 32: 475-9.

PubMed ID: 17110903 CLOSE

CLOSE

Cheung BM, Wat NM, Man YB, et al. Development of diabetes in Chinese with the metabolic syndrome: a 6-year prospective study. Diabetes Care 2007; 30: 1430-6.

PubMed ID: 17337491 CLOSE

CLOSE

Lear SA and Gasevic D. Ethnicity and metabolic syndrome: implications for assessment, management and prevention. Nutrients 2019; 12: 15.

PubMed ID: 31861719