Other Tools (WHO, EGIR and AACE)

Evaluating CMR - Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes/CVD RiskKey Points

- WHO was the first major organization to produce a definition of the metabolic syndrome that focused mainly on insulin resistance, whose diagnosis requires an oral glucose tolerance test.

- WHO criteria also proposed that microalbuminuria as a marker to identify high-risk patients with the metabolic syndrome.

- In response to WHO, EGIR sought to establish criteria that would be easier to use in clinical practice. EGIR makes measuring insulin resistance mandatory.

- The AACE position does not provide a specific scoring system for diagnosing the “insulin resistance syndrome”. Insulin resistance is at the core of AACE criteria, while waist circumference is not considered a diagnosis criterion.

- These organizations acknowledge that their diagnosis tools can be refined and that further research is needed to improve diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome in clinical practice.

WHO Definition and Criteria

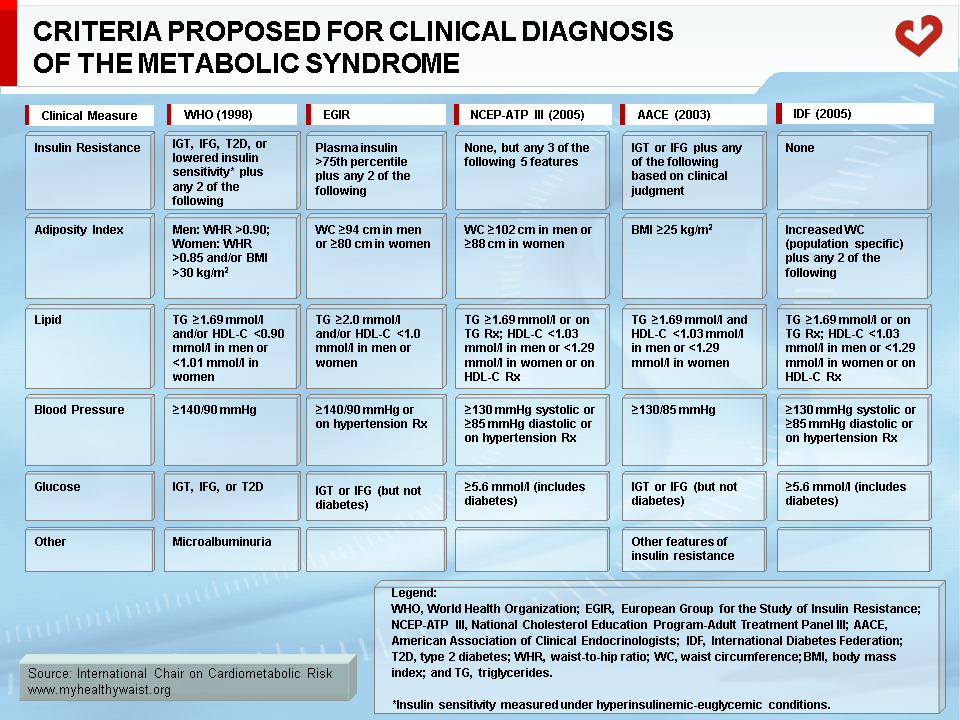

In 1998, the World Health Organization (WHO) was the first major organization to propose a definition of the metabolic syndrome (Table) [1]. In accordance with the syndrome X concept introduced by Reaven [2] (a combination of elevated fasting triglyceride and insulin concentrations, reduced HDL cholesterol levels, and raised blood pressure, with insulin resistance as a common denominator), the WHO definition also identified insulin resistance as the most common etiological factor behind the clustering abnormalities of the metabolic syndrome [2]. An index of glucose intolerance, impaired glucose tolerance, or diabetes and/or insulin resistance (insulin sensitivity measured under euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic conditions) was therefore a necessary WHO criterion for clinical diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome. Insulin resistance also had to be accompanied by at least two other criteria from among the following: raised blood pressure (≥140/90 mmHg), increased plasma triglyceride (≥1.7 mmol/l (150 mg/dl)) and/or reduced HDL cholesterol levels (<0.9 mmol/l (35 mg/dl) for men and < 1.0 mmol/l (39 mg/dl) for women), obesity as estimated by waist-to-hip ratio (>0.90 for men and >0.85 for women) and/or body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 for both sexes, and microalbuminuria (urinary excretion rate ≥20 μg/min or albumin-creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g).

The original WHO recommendations were intended to serve as working guidelines for research purposes. They were not designed to provide an exact definition for clinical diagnosis. The initial recommendations have remained controversial for a number of reasons. First, debate continues as to whether microalbuminuria is a necessary component of the metabolic syndrome. Although microalbuminuria is a marker of endothelial dysfunction and a predictor of increased cardiovascular risk, its relationship with the other components of the metabolic syndrome and the need to include this criterion in the clinical diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome are not firmly established [3,4]. Controversy also surrounds the use of waist-to-hip ratio versus waist circumference alone. It has been shown that waist circumference better indicates visceral adipose tissue accumulation (as measured with computed tomography, the gold standard method) than waist-to-hip ratio which is an index of relative abdominal fat deposition [5]. In addition, insulin resistance must be assessed for the metabolic syndrome to be properly diagnosed using WHO criteria. The preferred method is the clamp technique. Because this technique requires time and technical expertise, it was acknowledged that the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp would never be used by health professionals in clinical practice to screen for the presence of the metabolic syndrome in asymptomatic individuals. Moreover, apart from the European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR), very few epidemiological studies have measured subject insulin sensitivity with the clamp technique. It is therefore hard to develop large databases to generate population-based data on insulin resistance assessed with this technique [6]. In its 1998 statement, WHO stressed that the metabolic syndrome could be present for up to 10 years before any measurable glycemic disorders were detected, underlining the fact that individuals with normal glycemic control could still be at increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) or type 2 diabetes risk if they show other features of the metabolic syndrome. WHO called for the early detection and aggressive management of the metabolic syndrome to prevent related chronic diseases. The WHO group also called for future research in this area in order to understand and integrate the relevance of each component of the metabolic syndrome.

EGIR Definition and Criteria

EGIR published its own clinical criteria for the metabolic syndrome in response to the provisional report from the WHO consultation in 1999 (Table) [7]. EGIR’s approach was described as very “glucocentric” [8]. It has the advantage of being simple for ready use in clinical practice and epidemiological studies. Since there were “non-metabolic” abnormalities included in the metabolic syndrome criteria, EGIR felt that it should be labelled the “insulin resistance syndrome.” EGIR also saw insulin resistance as the core component of this syndrome. EGIR hypothesized that the insulin resistance syndrome was a constellation of mild abnormalities that worked in conjunction to considerably increase CVD risk. To facilitate diagnosis of the insulin resistance syndrome, EGIR criteria do not require the use of the clamp technique. As fasting insulin levels are one of the best markers of insulin resistance, EGIR suggested that insulin resistance be defined as the presence of fasting hyperinsulinemia (i.e., the top 25% of the distribution of fasting insulin levels in non-diabetic individuals).

According to EGIR, the insulin resistance syndrome should be diagnosed if insulin resistance is observed with two or more of the following abnormalities: fasting plasma glucose concentrations ≥6.1 mmol/l without diabetes, blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or treatment for elevated blood pressure, triglyceride levels >2.0 mmol/l (177 mg/dl) or treatment for elevated triglycerides and/or HDL cholesterol levels <1.0 mmol/l (88 mg/dl) or treatment for reduced HDL cholesterol levels, or an increased waist circumference (≥94 cm for men and ≥80 cm for women). EGIR criteria for blood pressure and dyslipidemia were drawn from the report of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention, which suggested that proposed cutoff values for blood pressure, triglyceride, and HDL cholesterol levels were associated with increased coronary heart disease risk [9]. Regarding obesity criteria, EGIR did not incorporate BMI in its diagnosis variables because the association between BMI and insulin resistance is not very clear, obesity being heterogeneous and not always associated with insulin resistance [10]. In addition, waist-to-hip ratio was omitted and waist circumference included since it is a better correlate of visceral adiposity than waist-to-hip ratio [5]. EGIR also excluded microalbuminuria from its criteria since the relationship between microalbuminuria and insulin resistance is not clear.

AACE

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) presented its official position on the “insulin resistance syndrome” in 2003 (Table) [11]. Unlike WHO and EGIR, AACE deliberately chose not to provide a specific definition of the insulin resistance syndrome, suggesting instead that diagnosis should depend on individual clinical judgement. AACE’s decision was based on the fact that the field is evolving rapidly and that it did not feel comfortable making a firm decision on proposed criteria cutoff values until more data was available. Regarding criteria to be included, AACE adopted the same clinical criteria as the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III or ATP III) for blood pressure and lipid criteria (which were also endorsed by the International Diabetes Federation). Blood pressure above 130/85 mmHg, triglyceride concentrations above 1.7 mmol/l (150 mg/dl), and HDL cholesterol concentrations below 1.04 mmol/l (40 mg/dl) for men and below 1.29 mmol/l (50 mg/dl) for women are therefore abnormalities of the insulin resistance syndrome. AACE also stated that fasting plasma glucose concentrations between 6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl) and 6.9 mmol/l (125 mg/dl) and plasma glucose concentrations between 7.8 (140 mg/dl) and 11.1 mmol/l (200 mg/dl) after a two-hour glucose challenge should be considered another syndrome abnormality. The two-hour oral glucose tolerance test is recommended for at-risk individuals who do not meet the proposed criteria for the insulin resistance syndrome. The Task Force appointed by AACE suggested that other criteria should be added or revised for assessment of the syndrome.

These modifications include recognition of the limitations of fasting glucose values and recognition of the merits of the oral glucose tolerance test. In describing syndrome etiology, the Task Force remarked that obesity should not be seen as a consequence of insulin resistance, but more akin to a physiological factor affecting insulin sensitivity. Obesity should therefore be considered a causal risk factor of the insulin resistance syndrome. The Task Force also recommended adding BMI as a measure of obesity. It felt that waist circumference did not provide sufficient additional information on overall risk, though it does view abdominal obesity as a prevalent form of insulin resistance. The Task Force also called for obesity cutoffs to be adjusted for ethnicity and ethnicity per se to be considered a risk factor. Moreover, the Task Force suggested expanding the list of at-risk individuals and the list of associated disorders, such as familial history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, CVD, personal history of CVD, polycystic ovary syndrome, gestational diabetes, and acanthosis nigricans. The AACE report also noted that physical inactivity is closely tied to insulin resistance and recommended early and more aggressive lifestyle interventions aimed at improving fitness and nutritional status to prevent the harmful effects of the insulin resistance syndrome. In addition, the report identified pharmacotherapy as an important option although very few pharmacological compounds have been proven to prevent, delay, or treat insulin resistance syndrome. Given this, thiazolidinedione compounds should benefit from further research to establish their clinical utility in targeting the insulin resistance syndrome. Special focus should be placed on their cardiovascular safety.

Although NCEP-ATP III clinical criteria are the most widely used in studies evaluating metabolic syndrome-related CVD risk, some studies have investigated whether WHO, EGIR, and AACE criteria also indicate increased CVD and type 2 diabetes risk. The most relevant studies are summarized in the Comparison of Screening Tools section.

None of the NCEP-ATP III, IDF, WHO, EGIR, and AACE working groups claimed that their criteria were best at defining and classifying individuals with the metabolic syndrome (or insulin resistance syndrome). Each of them called for further research to improve assessment and recommended the use of criteria that take into account obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, blood pressure, and the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic state. They also agreed that the most promising treatment for the metabolic syndrome is lifestyle therapy because it works on both abdominal obesity and insulin sensitivity.

References

-

Alberti KG and Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 539-53.

PubMed ID: 9686693

-

Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988; 37: 1595-607.

PubMed ID: 3056758

-

Chugh A and Bakris GL. Microalbuminuria: what is it? Why is it important? What should be done about it? An update. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007; 9: 196-200.

PubMed ID: 17341995

-

Toft I, Bonaa KH, Eikrem J, et al. Microalbuminuria in hypertension is not a determinant of insulin resistance. Kidney Int 2002; 61: 1445-52.

PubMed ID: 11918751

-

Pouliot M-C, Després JP, Lemieux S, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagitttal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol 1994; 73: 460-8.

PubMed ID: 8141087

-

Hills SA, Balkau B, Coppack SW, et al. The EGIR-RISC STUDY (The European group for the study of insulin resistance: relationship between insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular disease risk): I. Methodology and objectives. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 566-70.

PubMed ID: 14968294

-

Balkau B and Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet Med 1999; 16: 442-3.

PubMed ID: 10342346

-

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome–a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059-62.

PubMed ID: 16182882

-

Wood D, De Backer G, Faergeman O, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Summary of recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. Blood Press 1998; 7: 262-9.

PubMed ID: 10321437

-

Farin HM, Abbasi F and Reaven GM. Body mass index and waist circumference both contribute to differences in insulin-mediated glucose disposal in nondiabetic adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 47-51.

PubMed ID: 16400048

-

Einhorn D, Reaven GM, Cobin RH, et al. American College of Endocrinology position statement on the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocr Pract 2003; 9: 237-52.

PubMed ID: 12924350

CLOSE

CLOSE

Alberti KG and Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 1998; 15: 539-53.

PubMed ID: 9686693 CLOSE

CLOSE

Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes 1988; 37: 1595-607.

PubMed ID: 3056758 CLOSE

CLOSE

Chugh A and Bakris GL. Microalbuminuria: what is it? Why is it important? What should be done about it? An update. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007; 9: 196-200.

PubMed ID: 17341995 CLOSE

CLOSE

Toft I, Bonaa KH, Eikrem J, et al. Microalbuminuria in hypertension is not a determinant of insulin resistance. Kidney Int 2002; 61: 1445-52.

PubMed ID: 11918751 CLOSE

CLOSE

Pouliot M-C, Després JP, Lemieux S, et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagitttal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol 1994; 73: 460-8.

PubMed ID: 8141087 CLOSE

CLOSE

Hills SA, Balkau B, Coppack SW, et al. The EGIR-RISC STUDY (The European group for the study of insulin resistance: relationship between insulin sensitivity and cardiovascular disease risk): I. Methodology and objectives. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 566-70.

PubMed ID: 14968294 CLOSE

CLOSE

Balkau B and Charles MA. Comment on the provisional report from the WHO consultation. European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance (EGIR). Diabet Med 1999; 16: 442-3.

PubMed ID: 10342346 CLOSE

CLOSE

Alberti KG, Zimmet P and Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome–a new worldwide definition. Lancet 2005; 366: 1059-62.

PubMed ID: 16182882 CLOSE

CLOSE

Wood D, De Backer G, Faergeman O, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Summary of recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. Blood Press 1998; 7: 262-9.

PubMed ID: 10321437 CLOSE

CLOSE

Farin HM, Abbasi F and Reaven GM. Body mass index and waist circumference both contribute to differences in insulin-mediated glucose disposal in nondiabetic adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 83: 47-51.

PubMed ID: 16400048 CLOSE

CLOSE

Einhorn D, Reaven GM, Cobin RH, et al. American College of Endocrinology position statement on the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocr Pract 2003; 9: 237-52.

PubMed ID: 12924350